Mentally Mutilated

Jan 21, 2014

I have been mentally mutilated beyond all hope of regeneration.

When I was a small child, no more than three, my parents came into my room and placed a machine. From the outside, the machine was an innocuous piece of tan plastic wrapped around a heavily shielded interior, powered by (like the Terminator) a 6502 CPU. They plugged the machine into a hulking cathode ray tube. The tube was set in a wood veneer box adorned with a silver plastic strip dotted with inscrutable knobs.

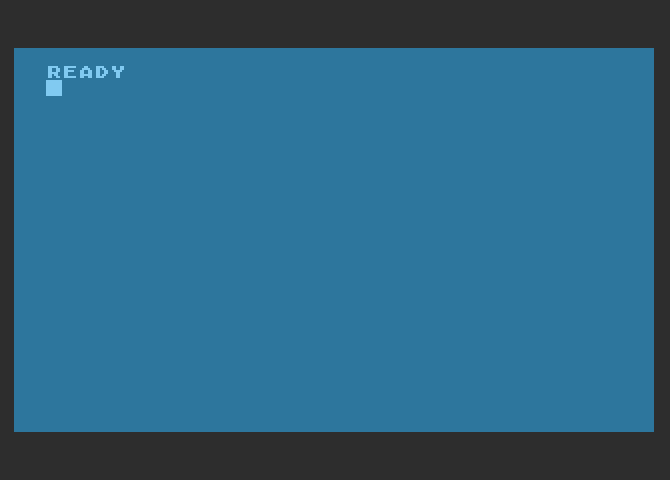

I think my parents must not have known about the dangers of this machine. At least, I hope they did not. When powered on, the machine would cause an electron gun located within the attached cathode ray tube to fire, accelerating and directing an electron beam. In its standard configuration, the machine was an instrument of mental mutiliation. The electron gun would fire and display this:

That hostile READY prompt was the sign that Atari BASIC was running and ready for input. The machine was an Atari 400, and the lack of instruction, of any sense of what you can or should do, harkens to the era where reading a spiral-bound printed manual was an expected part of the computer experience.

There was no escaping BASIC with these 8-bit computers. It was an expected, normal part of the experience, even though these machines were built several years after Edsgar W. Dijkstra warned,

"It is practically impossible to teach good programming to students that have had a prior exposure to BASIC: as potential programmers they are mentally mutilated beyond hope of regeneration."

The surest sign that I have been mentally mutilated is this: knowing (and respecting) Dijkstra’s opinions and the many problems with BASIC, I have absolutely no regrets about being exposed to it. BASIC is why I started programming, it is what got me into more and different and (yes) better languages. BASIC is why I am still a programmer so many years after I first overcame the hurdle of an opaque READY prompt and a block cursor. BASIC is why I am a good programmer.

The journey of a thousand miles begins with learning to walk

Atari BASIC, like the Microsoft BASICs available for other computers of that era, was a truly fantastic exploratory programming environment. You turn the computer on, you type a command, something happens. As a child, the immediacy and power of a single command provided enormous encouragement to continue, to do more, to see what else I could do with this thing I had discovered. It was a thrill.

Make the computer echo text back to you with the PRINT command. Make the computer play an awful, screeching noise with the SOUND command. When I found the GRAPHICS, PLOT, and COLOR commands, I was suddenly drawing on the screen. The computer came with simple, powerful commands that had immediate, obvious effects. And it wasn’t just that the rewards for exploring beyond the READY prompt were immediate; they built.

The complications and depth of the computer emerged from the simple, immediately understandable concepts as I sought to build more and better. The video games that I voraciously consumed showed what was possible. I could see the relationship between what I had accomplished and real programs that were (perhaps only in my imagination) just in the offing.

There were, of course, many missteps and errors on the way to learning. But for these kinds of exploratory programs, Atari BASIC provided the ultimate undo. When I made some obscure mistake, I could simply reset the computer and be instantly back to a clean slate, as if I’d never broken anything at all. Exploration and tinkering were all reward, no risk. Sure, the work that I had done was gone, but everything was back to working. And children aren’t particularly noted for their willingness to return to the same thing day-after-day, gradually improving on it.

The interesting thing about these BASICs was that for all their exploratory power, they were “real” languages: you could write most kinds of programs in them if you were clever enough, and they were easy to share with other users of the same computer. Get your hands on an Antic magazine, and there were programs you could (albeit tediously) key in.

These BASICs provided a sense of instant gratification, a sense of no risk of irrecoverable harm to the computer, and the ability to extend to larger programs. For its poor support of structured programming, these larger programs would be a pain to write and a nightmare to maintain. But, for me, the language’s strength was that it made me want to build larger programs, and I could once I wanted to.

Brain surgery by robotic turtles

If I avoided the mental mutilation at the hands of BASIC that Dijkstra so sternly warned against, it was perhaps due to Atari Logo’s judicious introduction of structured programming. In Logo, you learn how to use procedures, recursion, and functional concepts. You learn something of scope and context. And, best of all, you learn it in a respectable way because Logo has a top-notch pedigree: Logo is a Lisp, albeit tailored for teaching programming concepts.

Despite its serious academic parentage, Logo improved upon the immediacy and exploratory feel of early BASICs through a somewhat silly premise. Logo’s “turtle graphics” provided a sort of graphical mode that presented a directional cursor, represented by a turtle sprite, that you could manipulate through simple commands as if it were a programmable robot. The turtle was equipped with a pen so that when you issued the command FORWARD 50, the turtle would crawl forward (in whatever direction it was facing) 50 pixels, drawing a line from its old position to the new.

You could learn the commands to rotate the turtle by degrees, change the color of the turtle’s pen, and cause the turtle to pick up its pen so that it could move about without drawing. With these primitives, and a little imagination and exploration, the turtle could draw simple shapes like triangles and rectangles. Using subroutines and recursion, you could easily build more complex figures from simpler shapes.

As a clunky cartridge that I could slot into my computer, there were few complications or risks associated with Logo. As with BASIC, if I messed everything up, resetting the computer got me back to a clean slate. Something lost but nothing broken.

On the other hand, I have trouble imagining how one would’ve written much real software in Atari Logo. I never tried, and I shouldn’t doubt that someone did it. But if it had a mode for getting out of the exploratory environment, I never found it. For me, at the time, this was a good trade: a better introduction to important concepts, but a lower overall ceiling.

Through the glass ceiling

If you look at historical Logo, you might find in turtle graphics a sort of quaint, half-baked sort of object orientation. There is only one object (at least, in Logos that have only one turtle), and the methods for interacting with it are primitive and global, but the outlines are there. And, indeed, Logo influenced Smalltalk and has continued to exert its influence on modern learning environments (like EToys and Scratch) built in Smalltalk.

Yet Smalltalk is a different animal. Sure, it allows for the kind of exploratory programming that Logo and BASIC excelled at. But there’s something bigger going on. BASIC let you make things happen, Logo showed you the concepts for writing large programs. In Smalltalk, you inspect and explore a large, real, running program. You are exploring and changing the very program you are within: Smalltalk itself.

When you wonder how something is built in Smalltalk, you can simply navigate to it in the browser and see its code. Everything save for the lowest level of primitives (things necessarily implemented below the Smalltalk level) is there for you to see.

This power derives in large part from Smalltalk’s conceptual simplicity. There are objects. They listen for messages and respond to them when they are received. There are blocks of code (like messages) that are only executed when something asks them to run. And that is pretty much it. A class is an object, booleans are objects, and even conditionals are implemented as messages on booleans (#ifTrue:else:) that take blocks. Whether or not this simplicity aids in learning the language, it certainly helps in designing an environment that can be inspected and explored.

Smalltalk has been criticized for being too far removed from the “normal” computer environment. While you can write very real programs in Smalltalk, they are part of the Smalltalk environment and not normally treated as a separable executable easily delivered to others. This is similar to my early critique of Logo: how do you escape the learning environment?

Smalltalk’s answer to this question is that you do not. The entire environment is persisted to an image, and your code and data are part of the environment as much as anything else is. You work in and modify the image. You can ship your code as a sort of packaged delta that can be applied to other people’s images. While there are Smalltalk implementations that permit building stand-alone executables from your code, this is a secondary mechanism, orthogonal to Smalltalk’s virtues.

There are two more significant trade offs with Smalltalk. The first is that you have to seek it out and install it. Atari BASIC was just there. Logo and Smalltalk both needed to be obtained, and Smalltalk needs to be installed. Of course kids know how to do all this stuff, but in the case of a programming language environment, they don’t know that they want to.

The second trade off is that Smalltalk loses the simple assurance that you can easily reset to a clean, working state. While reversion is possible, work is involved. And while safeguards are in place, nothing really prevents the stubborn or careless from (perhaps subtly) hosing their image and then persisting that change.

All this brings us back around to the BASICs of the 8-bit era. For all its problems and faults, these BASICs were there, at your finger tips, ready to explore, with a low barrier of entry, and in a way that let you play without serious consequence. As you got better, you could write larger programs.

The pain of writing those programs might put you off BASIC, might lead you to other languages. This could, perhaps by some miracle, make you into a good programmer, one of the exceptions that proves Dijkstra’s rule. Or perhaps, like me, you’re just mentally mutilated beyond all regeneration.

Share